At COP21 in Paris, 23-year-old filmmaker Slater Jewell-Kemker will present clips of her first feature-length film An Inconvenient Youth, which she began shooting when she was fifteen years old. Described as An Inconvenient Truth meets Boyhood, the film follows the rise of the global youth climate movement.

What inspired you as a five-year-old to shoot films?

I was born in Los Angeles in 1992, a time when a lot of people were inspired by the Internet and were looking at the possibilities of how to use this powerful tool in a positive way. My mom’s friend Jeanne Meyers, who created the My Hero project, gave me my first camera and arranged for me to meet with the Vietnam War veteran and peace activist Ron Kovic. I sat in his lap while he wheeled me around his apartment talking about peace and showing me his artwork and photographs. I’ll never forget how kind and gracious he was with this little kid haphazardly filming everything. As little kids we gain this kind of emotional intelligence and understanding about other people and the world around us through stories. Being so young and exposed to people like Ron Kovic, Jeanne Meyers, and Kathy Eldon (Creative Visions Foundation) kind of planted this seed in my head that we’re all connected and that we’re all family and that, yes, we CAN make a difference in the world around us.

As a very young environmentalist, you interviewed stars and well-known scientists such as Leonardo DiCaprio and Jean-Michel Cousteau. Are adults more open to children?

As a very young environmentalist, you interviewed stars and well-known scientists such as Leonardo DiCaprio and Jean-Michel Cousteau. Are adults more open to children?

I think people are open to children and talking about the world in a more honest and open way because that’s how children look at the world, naturally. We ask questions, we are curious. We look at the world around us without bias. When I was interviewing Jean-Michel, I was thirteen and he told me: “I have given up on the species called adults. I only talk to young people because I can have a meaningful conversation with them, and I don’t have to go through the ritual of flirtation that basically kills their willingness to open up more. They are willing to let themselves be vulnerable and emotional.”

Where have you traveled as an environmental filmmaker?

I’ve been to youth conferences in Slovakia, the Czech Republic, the Netherlands, New York and Japan. I’ve traveled to agricultural communities in Nepal, South America and Northern Alberta. When you follow the story of climate change, you follow the story of how our world is changing and of how we, as people, are changing. It’s a global issue. Sometimes it affects one nation more than others, but eventually we’re all going to be affected.

Was the COP in Copenhagen in 2009 a turning point for you?

Was the COP in Copenhagen in 2009 a turning point for you?

Copenhagen was being touted as a huge moment. World leaders would finally come together and created a fair, ambitious, and binding deal that would lead all of humanity into a more sustainable and fair world: This was the story that was being sold by corporations like Coca-Cola with their “Hopenhagen — Open a Bottle of Hope” campaign. It was everywhere. It felt like: “Wow, maybe this really is the moment. Maybe we can get everything that we’ve been fighting for.” There was a lot of momentum building towards COP15 — and then the bubble of delusion burst.

Did you expect a policy change?

It shouldn’t have been a surprise that governments found it difficult to work together. And it shouldn’t have been a surprise that they were digging in and putting their own national interests ahead of moving together for the global community. But it really was devastating. You look at the science and you look at anecdotal evidence and it’s saying very clearly, with a loud voice, that we have a very small window of opportunity to change the way we live with each other and the planet in order to adapt to climate change. We’ve now gotten to the point where we can’t reverse climate change, but we can still lessen its effect. We can still adapt in a way that is sustainable and efficient and that will ensure our survival. It’s cutting it very close, though.

Do you think that the warnings were heard?

Do you think that the warnings were heard?

Seven years ago scientists were saying that we have maybe five to ten or fifteen years at most to do something; now, seven years later, a lot of people are getting to the point where they’re wondering whether we can we trust this system or not, whether can we trust the UN Climate Change Conferences, because they told us seven years ago that it was all going to happen, but now it’s seven years later and they’re saying the same thing. For me, and I think for a lot of other people too, we’ve come to the point in our thinking of “Okay, we gonna give you this opportunity. It’s either all gonna happen here or it’s going to be another Copenhagen and then… we’re gonna have to find another way to do this. I’m 23 years old, they’ve already been speaking all my life, it’s unacceptable to not have a deal already.

What is the essence of this experience?

Copenhagen has been inspiring, but frankly, we can’t let it happen again. It’s a brutal reminder of the ticking clock of climate change, and it hopefully shows that we can do better.

I was just watching a video clip of the Filipino negotiators at COP19, not too long after super typhoon Haiyan. A delegate broke down in his address to the conference members and delegates and was saying: “If not us, then who? If not now, then when? If not here, then where? What my country is going through due to this climate-related event is madness. The climate crisis is madness. We can stop this madness. It is the 19th COP but we might as well stop counting because my country refuses to accept that a COP30 or a COP40 will be needed to solve climate change.” That was two years ago.

Do you still have any hopes for the COP21?

Do you still have any hopes for the COP21?

You have to have hope or you’ll go crazy. I am cautiously optimistic about COP21 because there is a part of me that says “There’s still a chance” and you take it in with the idea that maybe everything could work out and we can finally start on this course to change how we live. But I’m not looking at it as the only solution.

When will your first feature-length film An Inconvenient Youth be shown?

I’ve been making it since I was fifteen and it ended up taking over my life a bit. My team and I are hoping to premiere the complete film next summer in May. At COP21, I’m going to show a 30 minute version that includes the journey of the last seven years, but also the most recent trip to Northern Alberta where the tar sands industry is located. It’s home to the world’s largest industrial project on Earth. A lot of climate activists are looking at it as a climate bomb — that if the carbon in the oil sands is released, then we would have no hope of adapting.

Has your film be growing in step with your own experiences?

Has your film be growing in step with your own experiences?

The film started off when I was fifteen visiting an environmental summit in Japan as a young Canadian youth delegate who was concerned about the environment who made new friends in Bangladesh and learning how my life can negatively impact someone half way around the world. I am learning about sustainability and adaptation in the UN which is leading me back to the simple connection between climate change and the environment and our addiction to oil. Because of our addiction to oil, we have significantly damaged not only the planet and our own health, but we have also caused the climate to be changing as rapidly as it is now. The film is really coming back to that awareness and asking the question: What’s the bottom line? How far are we willing to go?

Photos: © Courtesy of An Inconvenienth Youth Production

Robert Redford

Robert Redford Hannes Jaenicke

Hannes Jaenicke Nic Balthazar

Nic Balthazar Nadeshda Brennicke, Actress

Nadeshda Brennicke, Actress Darren Aronofsky, Director, Noah / Jury President, 65th Berlin International Film Festival

Darren Aronofsky, Director, Noah / Jury President, 65th Berlin International Film Festival Tim Bevan

Tim Bevan Thekla Reuten

Thekla Reuten Rachael Joy

Rachael Joy Nikola Rakocevi

Nikola Rakocevi Nadja Schildknecht

Nadja Schildknecht Michael Bully Herbig

Michael Bully Herbig Lars Jessen

Lars Jessen Helen Hunt

Helen Hunt Douglas Trumbull

Douglas Trumbull Dieter Kosslick, Director Berlin International Film Festival

Dieter Kosslick, Director Berlin International Film Festival Benoit Delhomme

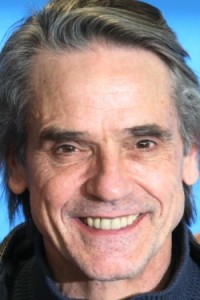

Benoit Delhomme Jeremy Irons

Jeremy Irons